“The world of thoughts, ideas,” Aunt Hilda began again slowly, as though groping for the right words, “is a very real one. There are many other worlds, you know, besides the one we see. Indeed, perhaps we all live in slightly different worlds—I don’t understand these things. But I think I have made a pathway, an opening, into the unknown and, Liz, I’m very much afraid.”

Another day, and another book I recall from my childhood turns up in an American edition in a Scottish second-hand bookshop. Last time, I found a copy of one of John Ball’s “flying-boats in space” juvenile novels. This time, it’s one of Joan North’s fantasy novels.

North wrote four books for children and young adults: Emperor Of The Moon (1956), The Cloud Forest (1965), The Whirling Shapes (1967) and The Light Maze (1971). Emperor Of The Moon was aimed at younger children—it involves comic adventures and magic wands. Then, after a gap of nearly a decade, North returned with the novels for which she is most fondly remembered—aimed at the younger end of the Young Adult market, these feature protagonists who are living out ordinary contemporary lives until they find themselves threatened by an episode of High Strangeness. North said she was interested in using her writing to explore psychological “Inner Space”, and the result carries a hint of 1960s psychedelia, combined with the stirrings of what Bob Fischer calls the “Haunted Generation” experience of 1970s childhood. It reminds me most strongly of the ITV television series Sapphire and Steel (1979-1982)—as Aunt Hilda intimates in my quotation at the head of this post, it’s seldom good news when disturbing stuff from Elsewhere leaks into our own world.

North was an English writer, and her stories feature English children in English settings, but to judge from the second-hand book market her three young-adult novels seem to have seen much larger print runs in the United States, all published by Farrar, Straus & Giroux. The British editions are almost forgotten, and generally difficult to find.

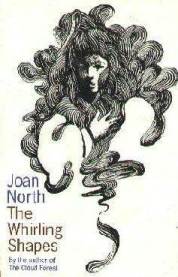

So my copy of The Whirling Shapes is the American edition, published the year before the UK edition. While it was nice to find and reread, it’s also a bit disappointing. Mainly this is because my memory is of the UK edition, published by Rupert Hart-Davis, and in particular the illustrations by political cartoonist John Jensen. So I’ve cheated a little and offered you Jensen’s sprightly cover illustration at the head of this post. The US edition is unillustrated, and the cover looks like it might have been stolen from a dreamy psychedelic folk album. The other problem with the US edition is that the editors have seen fit to “translate” it into American English. It’s all fine and dandy to see grey spelled gray, but it’s incongruous to read about English characters offering each other cookies, doing their math homework, taking out the garbage, and waiting fretfully for the mailman to arrive.

The story starts with fourteen-year-old Liz obliged to stay with her Aunt Paula and Uncle Charles for a year, while her mother recovers from tuberculosis in a sanatorium. Aunt and uncle are well-drawn—Paula always busy in a distracted kind of way, Charles shy and vague and only really happy when playing his piano. Also present are Liz’s sixteen-year-old cousin, Miranda, more interested in boys than schoolwork, and Great-Aunt Hilda Harbottle, a retired anthropologist who inhabits an upstairs flat, has led an exotic life, makes thumping noises at odd hours of the night, and appears to be slightly telepathic. The dramatis personae are completed by James Mortlake, a moody young artist who is obsessed with painting grey, whirling cloudscapes, and Miranda’s boyfriend-elect, Tom the medical student.

The High Strangeness starts in Chapter Two, during Liz’s first night in her new home, when she looks out of her bedroom window over the heath behind the house:

Only trees and bushes and grass met her eyes, except for the dark outline of a house set far behind the trees. Light poured from its windows. Liz felt strangely drawn to it; it looked both beckoning and beguiling, standing there alone.

Of course, it transpires that the house is not visible in daylight, and its existence is known only to Aunt Hilda, who fears that she may have accidentally conjured it into existence while handling a carved wooden egg fashioned from a sacred tree—the Tree of Dreaming True. And that’s when she delivers the little speech at the head of this post, afraid that she has opened a doorway into a dangerous other world.

And so it proves to be. Aunt Paula’s house is soon surrounded by a mist that seems to cut off its inhabitants from the outside world, and the mist is patrolled by whirling shapes of the kind painted by James Mortlake. Uncle Charles, steadfastly and unimaginatively try to go to his work, is quickly surrounded by these shapes, and simply disappears. And, as the mist encroaches on their home, our heroes discover that first the garden, and then the house itself, are gradually disappearing—they have a feeling that things are just stealthily vanishing while they aren’t paying attention. At this point in the narrative, North produces two striking images which stayed in my mind for fifty years—a tree in the garden which remains illuminated even though the street-lamp beyond it has vanished; and the moment when Liz stepped out of Aunt Hilda’s upstairs rooms …

… and peered out on the landing.

But there was no landing. The staircase and the rest of the house had vanished. Before her lay firm, leaf-covered ground which seemed partly the old familiar garden and partly a new extension of it.

No wonder it’s cold, she thought. We haven’t the centrally heated downstairs part to keep us warm.

Soon, our beleaguered party are going to have to flee across the heath, to reach that mysterious illuminated house …

That last quotation demonstrates one of the strengths of North’s writing—the utterly strange is juxtaposed with the entirely practical. Of course, if the heated part of your house had disappeared into limbo, the remaining rooms would start to get cold. And by pointing that out, North yanks the reader into the narrative in a way that a mere parade of weirdness would not have done.

And there’s a message, but one so subtly delivered it went right over my head when I first read this novel, in my early teens. It’s about paying attention—North was advocating mindfulness long before it became fashionable, and she sets this out gently in the latter part of the book, as her characters follow various redemptive arcs, and come to understand the nature of the world that has leaked into our own. The mist, the whirling shapes, the erosion of the house and garden, the disappearance of Uncle Charles—they represent the potential bleakness of a life lived without relishing the things and people around us; a life lived “mechanically”, to use North’s word.

It all ends happily, of course, including a resolution to Miranda’s comfort eating.

I did enjoy re-reading this one, and it made me want to seek out North’s other two novels in this genre. But her books are rare, and correspondingly expensive in the second-hand book market—I struck very lucky with the copy I found, it transpires. (There does seem to be a little cluster of relatively cheap British editions of The Cloud Forest in Australia, but the shipping costs to the UK render them not-so-cheap after all, for me.)

Maybe some day they’ll be revived in e-book form, but so far no luck on that.

or