Of rather uneven stylistic quality, but vast occasional power in its suggestion of lurking worlds and beings behind the ordinary surface of life, is the work of William Hope Hodgson, known today far less than it deserves to be. Despite a tendency toward conventionally sentimental conceptions of the universe, and of man’s relation to it and to his fellows, Mr. Hodgson is perhaps second only to Algernon Blackwood in his serious treatment of unreality. Few can equal him in adumbrating the nearness of nameless forces and monstrous besieging entities through casual hints and insignificant details, or in conveying feelings of the spectral and the abnormal in connexion with regions or buildings.

H.P. Lovecraft, “Supernatural Horror In Literature” (1927)

Two authors, admired (albeit slightly ambivalently in Hodgson’s case) by no less an authority than H.P. Lovecraft, who each wrote a series of short stories featuring what can best be described as “occult detectives”—exploiting the Edwardian enthusiasm for both detective stories and spiritualism.

William Hope Hodgson is probably best remembered for his novel of supernatural terror, The House On The Borderland (1908). Algernon Blackwood was a marvellously prolific author of weird short stories, collected in multiple volumes from The Empty House and Other Ghost Stories (1906) to Tongues of Fire and Other Sketches (1924). Blackwood lived into his eighties, but Hodgson was taken from us early—during the Fourth Battle of Ypres in 1918.

Five of Blackwood’s stories about his psychic doctor, John Silence, appeared together in 1908, in a collection entitled John Silence: Physician Extraordinary, which is now available in a Project Gutenberg edition. A sixth (shorter and strikingly out of character with its predecessors) then appeared in his collection Day And Night Stories (1917). As far as I’m aware, they were not then collected into a single volume until The Complete John Silence Stories was issued in 1997 by Dover.

Hodgson’s occult detective, Thomas Carnacki*, first appeared in a series of five stories published serially in The Idler magazine during 1910. These were collected, together with a sixth story, in Carnacki The Ghost-Finder (1913), which is also available in a Project Gutenberg edition. In 1947, August Derleth gathered together three more Carnacki stories (two previously unpublished) for an expanded edition issued under the Arkham House imprint.

Hodgson’s Carnacki stories have a formula. Like Sherlock Holmes, Thomas Carnacki lives at an imaginary address in a real street: 427 Cheyne Walk, which faces on to the Thames Embankment. He is, like Holmes, consulted by those who wish to retain his services in order to resolve an intractable problem—but for Carnacki, the problems are supernatural rather than criminal.

Then, in the aftermath of such cases:

Carnacki was genially secretive and curt, and spoke only when he was ready to speak. When this stage arrived, I and his three other friends, Jessop, Arkright, and Taylor would receive a card or a wire, asking us to call. Not one of us ever willingly missed, for after a thoroughly sensible little dinner, Carnacki would snuggle down into his big armchair, light his pipe, and wait whilst we arranged ourselves comfortably in our accustomed seats and nooks. Then he would begin to talk.

Carnacki then tells the story of his latest adventure to his four friends, reported as direct speech throughout. When the story concludes, they ask a few questions, and then are cheerfully dismissed by Carnacki with the phrase “Out you go!”

This strategy of reporting a first-person narrative as if addressed to a real audience is an immersively effective one, with Carnacki occasionally breaking off at moments of high peril to make quick asides to his friends.

Carnacki is a high-tech ghost-finder. There’s much use made of cameras and flash apparatus, and his Electric Pentacle comes into play frequently—the traditional star-shaped protective boundary, but composed of electrical discharge tubes rather than the customary chalk lines. But he is also, we are given to understand, steeped in occult lore. He offers frequent quotations from the fourteenth-century “Sigsand Manuscript”:

“In blood there is the Voice which calleth through all space. Ye Monsters in ye Deep hear, and hearing, they lust. Likewise hath it a greater power to reclaim backward ye soul that doth wander foolish adrift from ye body in which it doth have natural abiding. But woe unto him that doth spill ye blood in ye deadly hour; for there will be surely Monsters that shall hear ye blood cry.”

And, again like Sherlock Holmes, Carnacki offers frequent references to other cases, either his own or those of other (usually doomed) occult practitioners:

… what I term the ‘personal-sounds’ of the manifestation were so extraordinarily material, that I was inclined to parallel the case with that of Hartford’s, where the hand of the child kept materialising within the pentacle, and patting the floor. As you will remember, that was a hideous business.

Hodgson is expert at conjuring up weird and disturbing scenes:

… the darkness which filled the passage seemed to become suddenly of a dull violet colour; not, as if a light had been shone; but as if the natural blackness of the night had changed colour. And then, coming through this violet night, through this violet-coloured gloom, came a little naked Child, running. In an extraordinary way, the Child seemed not to be distinct from the surrounding gloom; but almost as if it were a concentration of that extraordinary atmosphere; as if that gloomy colour which had changed the night, came from the Child. It seems impossible to make clear to you; but try to understand it.

And Carnacki is seldom composed and rational during all this—he suffers from intermittent “funks”, sometimes flees the scene entirely, and vividly describes how fear makes his scalp feel tight, and his blood thunder in his ears so much that he worries he may be unable to hear some vitally important sound.

Another feature of Carnacki’s narratives is that things are seldom entirely resolved—he establishes that some malevolent entity, restless spirit, or (on occasion) mundane human agency is responsible for the manifestations he has investigated, but there’s almost always something he confesses he can’t explain fully. Some may find this frustrating, but for me Carnacki’s frank admissions of fear and uncertainty make his tales more convincing.

Blackwood introduces his hero Dr John Silence thus:

By his friends John Silence was regarded as an eccentric, because he was rich by accident, and by choice—a doctor. That a man of independent means should devote his time to doctoring, chiefly doctoring folk who could not pay, passed their comprehension entirely. The native nobility of soul whose first desire was to help those who could not help themselves, puzzled them. After that, it irritated them, and, greatly to his own satisfaction, they left him to his own devices.

John Silence’s practice is seldom entirely medical, however. Like Carnacki, he sorts out problems of a supernatural nature.

In order to grapple with cases of this peculiar kind, he had submitted himself to a long and severe training, at once physical, mental and spiritual. What precisely this training had been, or where undergone, no one seemed to know,—for he never spoke of it, as, indeed, he betrayed no single other characteristic of the charlatan,—but the fact that it had involved a total disappearance from the world for five years, and that after he returned and began his singular practice no one ever dreamed of applying to him the so easily acquired epithet of quack, spoke much for the seriousness of his strange quest and also for the genuineness of his attainments.

(Yes, that quotation contains only two sentences, the second of which is a jaw-dropping ninety words long. Even by the standards of his contemporaries, Blackwood was a wordy writer.)

The stories are sometimes narrated by Silence’s equivalent of Doctor Watson, a companion named Hubbard, who seems to have some knowledge of the occult himself. But in some stories Blackwood uses the viewpoint of an omniscient narrator. Blackwood’s original idea had been to assemble a set of stories dealing with various occult themes—hauntings, witchcraft, satanism, werewolves, and so on. But he was subsequently persuaded that the addition of a protagonist, common to all the stories, would produce a more coherent result. So Silence was a late addition to the concept, and this shows in Blackwood’s plots—Silence occupies a central role in only three of the six stories. In the others, someone else has the adventure (on one occasion, Hubbard), and Silence appears only to explain or resolve the problem.

This, combined with the reserved nature of John Silence, the adulation with which he is uniformly greeted, the third person narration, and Blackwood’s endless wordiness, makes John Silence a character that’s harder to engage with than Thomas Carnacki. While my copy of Carnacki’s adventures fairly bristled with bookmarks placed in anticipation of this review, John Silence afforded me sparser pickings.

Of all the stories, I found the first, “A Psychical Invasion”, with Silence very much centre-stage, the most interesting, and the only one that generated any sort of unease. Silence stakes out a haunted house, with the aid of a dog and a cat.

He has brought his pets along because:

He believed (and had already made curious experiments to prove it) that animals were more often, and more truly, clairvoyant than human beings.

And so it proves to be:

[The cat] had jumped down from the back of the armchair and now occupied the middle of the carpet, where, with tail erect and legs stiff as ramrods, it was steadily pacing backwards and forwards in a narrow space, uttering, as it did so, those curious little guttural sounds of pleasure that only an animal of the feline species knows how to make expressive of supreme happiness. […]

At the end of every few paces it turned sharply and stalked back again along the same line, padding softly, and purring like a roll of little muffled drums. It behaved precisely as though it were rubbing against the ankles of some one who remained invisible. A thrill ran down the doctor’s spine as he stood and stared. His experiment was growing interesting at last.

And so Silence finds himself sharing a room with an invisible, malevolent entity that his cat loves, and (it transpires) his dog hates and fears. (That’s cats for you.)

The slow working out of this plot is, for me, the high point of the entire collection.

Hodgson’s writing works better for a modern reader than does Blackwood’s, I think. There are sequences in Carnacki’s adventures that are almost cinematic, and full of urgency. Blackwood builds tension so slowly, and telegraphs his purpose so obviously, that it’s a bit difficult to get excited. For example, the scene involving the cat’s strange behaviour, above, is preceded by endless pages in which Silence and his companion animals sit around calmly waiting for something to happen. And before that, we’re treated to a well-observed, but hugely prolonged, dissertation on the relationship between this particular cat and dog. (They’re quite cute together, admittedly.) Hodgson is often criticized for his lack of characterization, and it’s certainly true that Carnacki’s companions are mere ciphers, present only to give Carnacki someone to talk to. But that’s the whole point—Carnacki needs to be chatting to trusted companions to make the narratives come alive in the way they do.

You can read or download the original six Carnacki stories at Project Gutenberg. Marcus Rowland hosts all nine stories on his excellent webpages devoted to Carnacki. (American readers should note his comment about copyright still applying to the later three stories in the USA, if they plan to download a copy.) And you can borrow a more recent edition of the full Carnacki collection from the Internet Archive.

You can find John Silence, Physician Extraordinary, containing all but the last story, at Project Gutenberg and the Internet Archive.

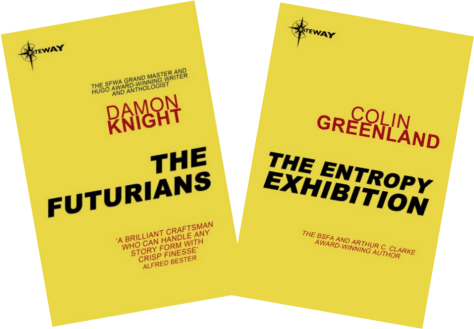

Both collections are also currently available in paperback and e-book editions, though the quality of layout and punctuation isn’t brilliant, from what I’ve seen.

* We don’t actually learn Carnacki’s first name until the fifth story, “The Searcher Of The End House”, when he is addressed as “Thomas” by his mother. Interestingly, however, The Idler gave his full name in the introduction to the first story printed. Presumably they were already in receipt of the fifth story, or perhaps Hodgson has provide some sort of outline of proposed plots in which he gave Carnacki’s full name.

or